Beginning in 2000, when there were promises of a more-democratic system and a stronger civil society, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) blossomed in Mexico, offering different social groups a new way to participate. In the international context of the previous decade, there had been a boom in alt-world movements and a worldwide explosion and expansion of foreign NGOs, some of which were present in Mexico and began holding the established powers accountable. In that same decade, and with increased strength thanks to the victory of a different political party, Mexican NGOs also became more vocal about issues related to development and transparency.

Although the first NGOs in Mexico were created in the middle of the eighteenth century, their public relevance took off with the development of the Internet and digital media, when their actions and claims spread all over the world. Particularly, NGOs emerged to fill voids lacking government attention, such as in health and education, promoting democracy and human rights, and tending to the most-vulnerable groups of society. Today, there are more and more NGOs in Mexico (around 28,000), but their aid approach has not changed much. Unlike their European and U.S. counterparts, they have not taken full advantage of the opportunity that supposes engaging with the private sector, partly because they think they hold contradictory positions.

However, since the Río 1992 Summit, it has been accepted that cross-sectoral alliances involving the state, businesses and civil society are one of the most-efficient means of bringing about significant changes to complex, intricate social and environmental problems. Particularly, the most productive alliances between NGOs and the private sector have come about mainly to promote environmental conservation, the creation of sustainable value chains, and the implementation of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programs and policies. NGOs have proven to be effective allies in mitigating business impacts on the environment and on local communities, and in creating innovative practices. The stronger the relationship, the more decisive the transformation has been.

But in Mexico, what is the likelihood of NGOs engaging with the private sector? How willing are NGOs to work with corporations? And what are the experiences so far? These are a few of the questions that led to theresearch project “NGO-Business Engagement in Mexico,”which I conducted in 2016 along with Dr. Dennis Aigner, professor at the University of California, Irvine, and financed by the University of California Mexico-U.S. Institute and CONACYT.

To obtain a general panorama, we surveyed 364 Mexican NGOs, of which 78% were identified as social NGOs and 22% as environmental. The survey asked about the level of engagement between NGOs and the private sector, the motivations behind it, some insight on how the engagement initiated, and the percentage of NGO employees and budget that are dedicated to private sector-related activities. We also evaluated some aspects relevant to building cross-sectoral trust, such as how much information NGOs make available to the public about their mission, their performance, and the media they use, as well as how much trust respondents have on institutions such as the government and the private sector, and whether they have experienced corruption in their activities with firms.

In general, the main findings of the study confirmed our hypothesis: In Mexico, only one-third of civil society organizations have had any type of engagement with the private sector in the last five years. Of the remaining organizations, very few taken a position that is openly contrary to businesses, thus showing a complete disconnection or indifference between the two sectors. This becomes problematic when we consider that the complex problems we face today—climate change, biodiversity loss, political instability, pollution, and others—cannot be solved by governments alone. Private actors, that is, NGOs and businesses, also share an essential responsibility in the development and implementation of creative alternatives and in the generation of knowledge and expertise that helps us to move toward fairer and more sustainable models.

Transactional Relations at Most

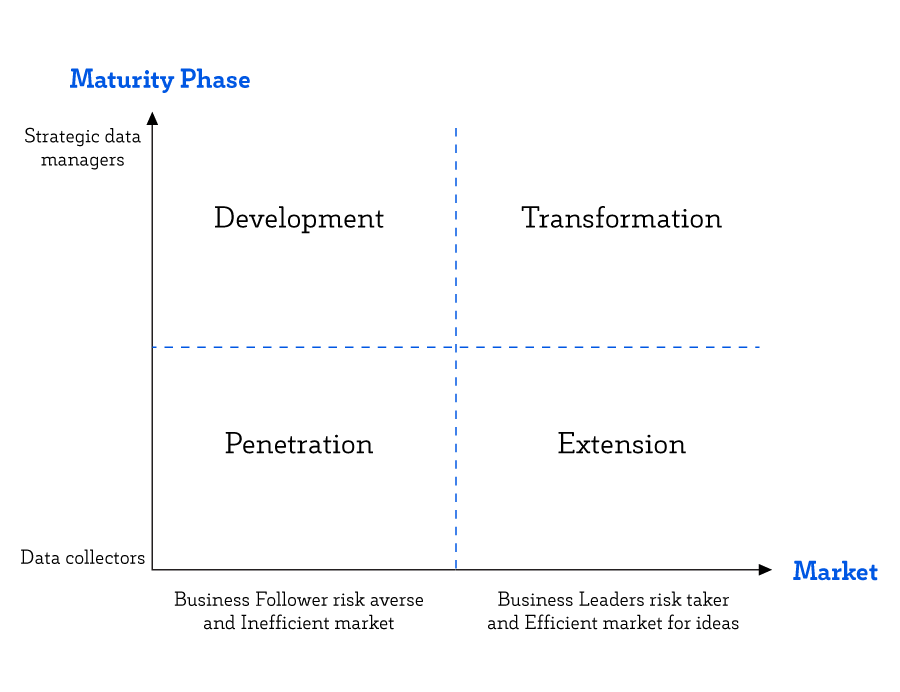

Previous studies on cross-sectoral collaboration have revealed that the depth of the commitment between NGOs and firms depends on the level of interdependence and the complexity of the interactions among organizations from both sectors. Accordingly, the engagement can be purely transactional, giving priority to fundraising through corporate philanthropy, or it can be transformational, aiming to change business practices or social structures.

- In Mexico, most NGOs establishtransactionalrelations with businesses mostly in the form of project implementation, consulting services, and participation in government-led initiatives. Even though this engagement goes beyond thephilanthropystage, most NGOs do not reach theintegrativestage, which includes NGO participation in consulting processes with the private sector or the co-design of CSR initiatives. Even fewer reach thetransformationalstage, which implies shaping public policy and pursuing change backed by civil society.

- Currently,transactional initiativesare focused on carrying out conservation, education, health, and social development projects, as well as raising awareness and providing environmental training. Such initiatives pursue narrow goals and are short-termed. On the contrary,transformational initiativesseek to generate new rules or management processes to achieve structural change. An example in this regard is El Triunfo Conservation Fund, which since its creation in 2002, brings together more than a dozen private actors, institutions, and communities to assure the conservation of El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve in Chiapas. Besides protecting the rich biodiversity of this forest area, the initiative has designed a model of shared management of natural resources, combining conservation and productive activities such as sustainable agriculture and ecotourism.

- Of the few NGOs that engage with the private sector, almost half of them do it out ofstrategic considerations, while the other half do it as a result of an unforeseen opportunity, implying that few NGOs have formal procedures to screen possible partners. Most NGOs perceive collaboration with the private sector as anopportunityto acquire and manage resources, to extend their networks, and to boost their reputation.

- Most NGOs believe that working with the private sector can represent a larger opportunity than a risk. They regard engagement as afeasible option, despite the different visions and goals of each sector, and they do not perceive firms having morepoweras an impediment for pursuing common goals.

- Generally speaking, NGOs are not completely sure that “businesses are atrustworthy partner,” even though most believe that they are more honest than the government and have not witnessed corruption within businesses first hand.

Absence of a Strategic Approach

Aspects of trust, transparency, and strategic alignment can hinder cross-sectorial collaboration. Assuming that transparency helps to build mutual trust, it is commonly believed that the more transparent an organization is, the more opportunities for collaboration it will have. But collaboration is also a result of certain strategic considerations at the organizational level. Is engagement with businesses aligned to the goals, model of change, and allocation of resources of the organization? Apparently not.

- Only one-fifth of the NGOs earmark aspecific budgetfor activities related to the private sector and most of them do not have employees dedicated to these activities.

- Even though 84% of the NGOs seem open to working with other actors, such as local communities, other NGOs, or the public in general, only 31% work with the private sector. This goes to show that the degree of “openness” of an NGO towards other groups in society does not determine the likelihood of engagement with the private sector.

- Less than half of all the NGOs surveyedpublish informationabout the activities they perform related with the private sector, and very few publish financial information or data about how they assess their projects internally. This prevents businesses from being able to identify the most effective and efficient organizations.

- Regardingtransparency, of the NGOs that make their information public, only 61% could be considered transparent based on the type and amount of information they publish. Of these organizations, fewer than half of them work with companies, which implies that being transparent is not a necessary condition for engaging with the private sector.

The Purpose of NGOs: A Model Unique to Mexico

Studies about collaboration between NGOs and businesses show that in many countries relations have shifted from a confrontational to a cooperative approach. Still, even though Mexican NGOs are also becoming more practical, flexible, and less dogmatic, they are far from building lasting relationships with businesses.

Our research shows that there are many areas of opportunity for NGOs when communicating with civil society, businesses, and other organizations. Even though they use social networks widely to disseminate their activities and goals, NGOs do not know each other. Let us now imagine how much work is required for businesses to identify trustworthy, competent allies to carry out programs with ambitious goals and a long-term commitment, both necessary to achieve positive, scalable, replicable effects that could bring about important transformations.

In particular, the results of our survey identified a broad lack of understanding about what NGOs actually do, their functions, and what their possible contributions to solving complex problems might be. Much has been written in other countries about the roles of civil society in denouncing unfair or incorrect situations (watchdogs), their ability to set little-known or poorly understood issues on the global agenda (agenda setters), their capacity as resource and contact intermediaries (brokers), and their contribution in the provision of basic or emergency services (providers).

But the functions of NGOs in Mexico and the goals they pursue are often not made explicit. Their most obvious contribution lies the realm of service provision, covering many needs that the government has left unattended for years. But perhaps less clear is their role in representing the interests of vulnerable, excluded, and minority groups in public or private decision-making processes, such as consultations about public policies, local community consent in the exploitation of natural resources, and international human-rights agreements, among others.

So, if in Mexico neither the degree of openness of an NGO towards other sectors of society, nor its degree of transparency and accountability determine its propensity to work with the private sector, what does?

The only factor that might have a significant influence on cross-sectoral collaboration is the strategic decision to integrate business engagement as a specific component of an organization’s intervention model or theory of change. That is, to openly and decisively seek corporate engagement as a means to achieve the organization’s ends. Models like this one have been adopted by international NGOs such as Conservation International, Oxfam, and WWF, which engage with the private sector to boost and gain leverage for their ambitious conservation, anti-poverty, and climate-action agendas, respectively.

Obstacles to Cross-sectoral Collaboration

Engagement is not free of obstacles and it is important for organizations that choose this alternative to keep this in mind. In this regard, we have identified at least two main obstacles that Mexican NGOs will have to face when opting to engage with firms.

The first obstacle has to do with overcoming the lack of knowledge and experience regarding:

- How to interact with the private sector,which includes defining intervention formats, project length, managing resources and workloads, dealing with power relations and reputational aspects, among others.

- How to choose adequate partners,including decisions about whether to engage with multinational or Mexican firms, to act at the national or local levels, and about whether to engage with one company at a time or several simultaneously.

- How to manage cross-sectoral projects,which refers to the type of organizational skills and expertise each project requires, as well as demands from the private sector regarding reporting, accountability, confidentiality, responsibility sharing, and more.

The second obstacle has to do with the political implications of openly engaging with the private sector, which might force NGOs to:

- Reconsider their positionor mission in order to move ahead with the common goals of the engagement, going beyond the organization’s particular goals or views of the situation.

- Become vulnerable to criticismfrom other “natural” constituents (i.e., the social groups they represent and other NGOs) because of their proximity the private sector, perhaps causing them to lose credibility in these social circles.

- Take a position against the status quoand the interests of dominant groups by means of fighting for the rights of vulnerable groups, environmental conservation, or other politically-sensitive topics.

To help overcome these obstacles, universities can play an essential role in building bridges between NGOs and the private sector by means of creating spaces of interaction and expanding their traditional spheres of action to jointly create solutions to complex problems. One example in this regard are the activities promoted by SUSTENTUS, EGADE Business School’s sustainability and entrepreneurship center, which promotes + Talento, a training course that motivates firms to hire people with disabilities and gives insight into how to develop inclusion policies. Another example includes research projects such as this one, where ten representatives of civil society and the private sector have participated as members of an advisory committee that helps to ensure that the study is socially relevant and that the information produced includes robust and actionable data and insights.

Despite the obstacles mentioned above, cross-sectoral collaboration is still considered one of the most-effective ways to address society’s most complex, intricate problems. Both NGOs and firms in Mexico could benefit from embracing this model as soon as possible.