How can the loss of competitiveness of the last six years be reversed?

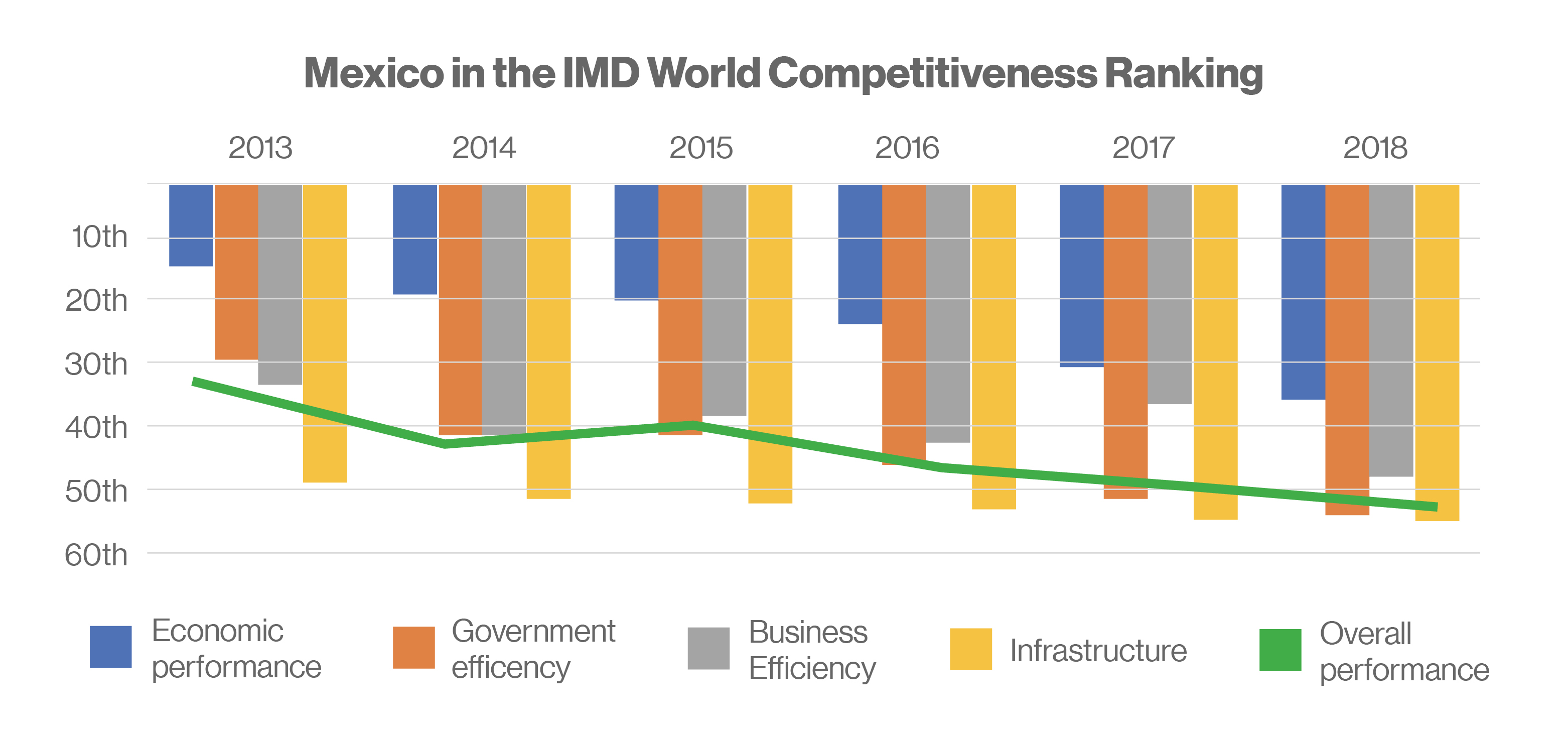

A few weeks ago, it was made known that between 2017 and 2018, Mexico dropped three places in the IMD World Competitive ranking, to 51st out of 63 countries. However, the news failed to emphasize that, according to this indicator, our country has actually lost 19 places in competitiveness over the past 5 years, from 32nd in 2013.

Competitiveness is a broad concept that, according to Arturo Bris –director of the IMD World Competitiveness Center–, expresses “the way in which countries, regions and companies manage their competencies in order to accomplish long-term growth, generate jobs and increase wellbeing.” According to the World Economic Forum, “A competitive economy is a productive economy, and productivity leads to growth, which, in turn, takes us to (higher) income levels and improved wellbeing.”

The IMD index contemplates more than 250 indicators correlated with competitiveness, since they operate in one of the three following ways: as factors that create the conditions for competitiveness, as competitiveness level indicators, or as variables that receive the direct effects of the level of competitiveness accomplished. Of the four major factors, the ones that have lost the most places are ranked as follows:

- Greatest loss in government efficiency (54th place): Worsened institutional and social schemes, which are determined by the degree of effectiveness of government actions. In particular, some of the most deteriorated components in this category are: growth of the informal economy, high levels of corruption and bribery, lack of transparency, risks to personal safety and property rights, limitations to the justice system, high homicide rate, elevated income and opportunity inequalities, tax evasion and difficulties in the creation of new companies.

- Decline in economic performance (35th place): Low dynamism in public and private investment, total and per capita domestic production, and formal employment; rise in inflation and cost of food; depreciation of the peso; and limitations in international trade, such as its high concentration in the United States and limited service exports. These latter two aspects assume a particular risk in face of the NAFTA renewal difficulties.

- Erratic behavior of business efficiency (48th place): Erratic, but with a downward trend. Interestingly, a decline in all the subcomponents of this factor can be observed, such as: productivity, efficiency, management competencies, financial position, and attitudes and values.

- Lowest loss in the factor infrastructure (55th place): Six places lost since 2013. This shows us that our infrastructure has traditionally been limited and has not increased at the same rate as in the rest of the world. Aspects such as basic infrastructure, health and environment, and education displayed the greatest losses.

Mexico's position in the IMD World Competitiveness Ranking, 2018.

There are, of course, strengths and positive behaviors in diverse components associated with Mexico’s productivity and competitiveness, which can serve as a foothold for developing a national crusade to recover the country’s competitiveness and productivity.

However, it is important that the new federal government, which will come into power at the end of this year, should develop and address a comprehensive agenda that will tackle the institutional, social, economic and political obstacles that have affected the competitiveness, productivity, growth and wellbeing of Mexico and its inhabitants. This is a challenge that urgently needs to be addressed with intelligence, courage and political will.