This paper argues that the U.S.’s turn toward protectionism and economic nationalism reflects a deeper strategic agenda to preserve its global dominance in an increasingly fragmented global order. While globalization delivers economic benefits, these gains are increasingly interpreted through the lens of geopolitical imperatives such as technological supremacy and containing China. The same is true of his border security policy. Drawing on classical geopolitical theories, the analysis reveals how U.S. policies under the second administration of President Trump (Trump 47) are likely to reshape North American integration, weaponize economic tools, and accelerate the shift from cooperative globalization to zero-sum competition. As the U.S. recalibrates its role, this paper challenges policymakers in Canada and Mexico to navigate an emerging paradigm where a new kind of pragmatism dictates U.S. actions.

1. The end of globalization: Power over profit?

1.1. The shifting foundations of U.S. policy

“Tariff,” President Trump once declared, is “the most beautiful word in the dictionary.” For decades, however, economists have considered it an ugly relic—an inefficient and costly barrier to free trade, which underpins the modern global economy. Yet, during Trump’s presidency, the U.S. turned away from its commitment to free trade, marking a seismic shift in economic policy that has endured after his departure and is likely to come back with force under his second term.

This retreat from globalization was not Trump’s invention. The first tremors were felt with the 2016 Brexit referendum, a populist revolt that shook the European Union to its core and questioned the very premise of economic integration. By 2018, economic nationalism had crossed the Atlantic with Trump’s election (Trump 45), signaling a departure from decades of U.S. leadership in promoting open markets. What many

hoped would be an anomaly, gained permanence under President Biden instead. In effect, far from reversing course, President Biden entrenched the tenets of Trump’s economic vision. Tariffs on China remained, the U.S. financial system was wielded as a weapon against Russia, and industrial policy was mobilized to reshore manufacturing capacity. Under Biden, the concept of “nearshoring”—relocating supply chains from Asia to the Americas—gained traction. This shift reflects less of a triumph of economic efficiency and more of a recalibration of global supply chains to mitigate geopolitical risks in an increasingly fragile and uncertain world. The COVID-19 pandemic further reinforced this view, as it laid bare the vulnerability of global supply chains.

While the global order may not yet be truly multipolar, the rise of regional powers like China and the strategic assertiveness of nations such as Russia, despite their structural limitations, signal a shift toward a fragmented and competitive geopolitical landscape. This emerging paradigm reflects not a clear transfer of power but an erosion of the cooperative framework that once underpinned globalization. Back in the 1990s, President Clinton’s campaign coined the mantra: “It’s the economy, stupid.” Today, geopolitics, not economics, dominates the stage, reshaping the priorities of nations and businesses alike. The once-stable foundations of globalization have fractured, unable to withstand the pressures of a world where U.S. leadership is increasingly contested but not yet replaced. Today, amid power plays and fractured consensus, geopolitics has overtaken economics as the primary force shaping the global landscape. The market's invisible hand still matters, but it now operates within the shadow of strategic rivalries and geopolitical maneuvering—“It’s Geopolitics, Stupid!”

1.2. The geopolitical hypothesis: The U.S. role in a fragmented world

This paper argues that economic fundamentals alone cannot explain the rise of protectionism and anti-trade policies that are eroding the pillars of globalization, including an open trade system. The central claim is that, despite the undeniable benefits of globalization, these gains are not enough to sustain free markets as a stable equilibrium.

The hypothesis is that the U.S. is pursuing strategic objectives to maintain its geopolitical dominance in a world defined by shifting power dynamics. Tariffs and economic nationalism are not mere policy quirks; they are part of a broader and more nuanced strategy aimed at preserving America's post-war global influence while constraining the rise of competing powers like China. While these measures can be

seen as efforts to reinforce U.S. dominance, they also reflect a defensive posture— seeking to hinder others from ascending to leadership rather than unequivocally consolidating its own. The goal may be to safeguard elements of U.S. hegemony, but this strategy reveals a readiness to accept short- and medium-term economic losses in exchange for long-term geopolitical primacy.

To understand these developments, this paper suggests revisiting classical geopolitical theories—specifically Mackinder’s Heartland theory and Spykman’s Rimland theory—as a framework for interpreting U.S. policies. These theories illuminate how non-economic objectives can take precedence over economic priorities. Importantly, this geopolitical hypothesis does not assume that policymakers explicitly craft strategies with Mackinder or Spykman in mind. Instead, it argues that leaders like President Trump operate with fewer constraints than their predecessors, allowing them to pursue bolder policies. Freed from rigid economic, political, and institutional limits, such leaders often confront deeper, immovable constraints—chief among them geography. President Trump, for instance, may not see himself as a geopolitical

strategist, but he cannot ignore the fact that the U.S. shares a border with Mexico. This geographic reality, indifferent to ideology or politics, inevitably shapes policy decisions. In this sense, geopolitics acts as a “hard constraint” that governs the actions of political and economic actors alike, although they do not necessarily pull in the same direction.

This argument is not a dismissal of economics. Instead, it underscores that the economy is not a self-contained system. It is embedded within a web of political and institutional frameworks, social and demographic dynamics, and the quasi-immutable realities of human and physical geography. For decades, these structures provided stability, allowing economic analysis to dominate. But as this stability frays, economic analysis alone becomes insufficient to explain or predict behavior. While economic actors still weigh costs and benefits, other forces are increasingly at play. Geography, in this context, emerges as the unchanging bedrock in a world of political, institutional, and social instability.

The rejection of free trade and globalization, coupled with the use of tariffs as tools to achieve non-economic objectives, should not be misconstrued as a sign of isolationism. Paradoxically, these actions reflect the U.S.’ determination to preserve its global leadership in the face of China’s rising influence, even at the expense of short- and medium-term economic gains. Trump 47 does not signify a retreat from the global stage but rather a recalibration of strategy to reaffirm U.S. dominance at any cost. This approach underscores a willingness to leverage America’s political, economic, and military power to counter emerging rivals and solidify its leadership in a competitive and fragmented global landscape. By prioritizing strategic imperatives over economic efficiency, the U.S. is signaling its commitment to defend its position as the central actor in the global order.

1.3. Distinctive elements of Trump 47’s geopolitical approach

The idea that geopolitical imperatives shape U.S. objectives is hardly new. During the Cold War, U.S. foreign policy was influenced by the ideological struggle between the capitalist West and the communist East—a rivalry that no longer exists. Today, there is a rapidly evolving U.S.-China geostrategic rivalry. Expectedly, in a second Trump administration (Trump 47), three distinct elements unique to today’s context will redefine these imperatives, making it crucial to avoid viewing this hypothesis as a mere throwback to mid-20th-century dynamics.

The first distinguishing factor is President Trump’s status as a true outsider, operating with fewer institutional and political checks. With a strong popular mandate from the 2024 election, Trump 47 is likely to face even fewer constraints than he did in 2017, making unilateral actions more common. Traditional diplomatic channels and multilateral frameworks may be sidelined altogether, as political and economic systems fail. Yet geopolitics, as an immovable force, will shape and limit his policies. A striking example of Trump’s outsider approach was his handling of NATO during his first term, where he castigated allies over defense spending and threatened withdrawal, breaking decades of bipartisan consensus. In a second term, this could escalate: Trump 47 might unilaterally reduce U.S. troop deployments or impose economic penalties on NATO members, bypassing multilateral agreements. While such moves reflect his transactional style, they would inevitably collide with geopolitical realities. A complete NATO withdrawal, for instance, could destabilize Europe and undermine U.S. strategic interests.

The second defining element is Trump’s hierarchical preference order. His “America First” ethos can be seen as a rigid framework that prioritizes U.S. global dominance more than anything else. Domestic security and political objectives override all other concerns, such as international cooperation, global trade, and multilateralism. This strict prioritization, described as a "lexicographic order," arranges objectives hierarchically, requiring higher-priority goals to be fully satisfied before lower-priority ones are considered. Like how words are ordered alphabetically—where the first letter takes precedence—this approach allows economic and institutional considerations to be sacrificed in pursuit of broader strategic goals.

This approach has tangible consequences. In the Arctic, U.S. efforts to dominate emerging maritime routes and resource reserves could strain relations with Canada, a key ally. A confrontation over navigation rights or territorial claims could weaken trust within the North American alliance. Similarly, Trump’s repeated attempts to purchase Greenland, despite rising tensions with Europe, exemplify his willingness to override traditional diplomacy in pursuit of strategic gains. Closer to home, Trump’s focus on migration control along the southern border could disrupt the deeply integrated U.S.-Mexico supply chains critical to industries like automotive and electronics. Prioritizing border security, immigration and drug traffic, over economic cooperation could harm both economies and undermine North

America’s regional competitiveness.

The third unique element of Trump 47 is his potential role as an accelerant of existing trends. The pivot from cooperative globalization to competitive geopolitics has been underway for years, but Trump’s unconstrained and transactional style could significantly hasten this shift. By prioritizing geopolitical goals over economic and diplomatic considerations, Trump is poised to amplify these changes within a

compressed timeline. One example is the U.S. effort to decouple from China in key industries such as semiconductors and green energy. While these initiatives have already begun, Trump 47 could escalate them dramatically, introducing aggressive tariffs, export controls, and reshoring incentives at a scale that might otherwise have unfolded more gradually. The global implications of such accelerated changes would be profound, reshaping supply chains and geopolitical alliances in ways that could reverberate for years to come. However, these shifts may not favor U.S. geostrategic interests; on the contrary, they risk unintended consequences, including economic disruption and geopolitical isolation.

1.4. Broader implications of U.S. strategic shifts

As the U.S. increasingly views its economic system through the prism of strategic advantage rather than global leadership and shared prosperity, the cooperative game of globalization is giving way to a zero-sum paradigm. The rise of regional trade blocs, economic decoupling, and the weaponization of financial sanctions all reflect this stark new reality.

Security imperatives and strategic competition now eclipse the incentives that once favored open markets, signaling a broader transformation in the global order. The promotion of liberal values, democracy, and nation-building—hallmarks of early 21stcentury neoconservatism—has faded as a guiding principle. Once framed as essential to global stability, these efforts are now secondary to securing national interests and preserving dominance in a fragmented and contested global order. This shift is also a response to the failures of such initiatives, as seen in Afghanistan and Iraq, where prolonged interventions failed to achieve intended outcomes, leading to widespread

disillusionment with these strategies.

This paper offers a balanced analysis of the trajectory of U.S. policy under a Trump 47 presidency. It neither endorses nor critiques these strategies but seeks to contextualize their implications within the broader dynamics of a shifting global landscape. The pressing challenges of our era—climate change, pandemics, mass global migration, and transnational organized crime—demand international cooperation and institutional alignment, yet such efforts are increasingly difficult in a fragmented geopolitical environment.

The drift from global collaboration toward zero-sum geopolitics risks deepening divisions at a moment when collective action is urgently needed. Rather than justifying these dynamics, this paper provides a conceptual framework to help policymakers and stakeholders make sense of them. By engaging with these realities, we can navigate the complexities of this new era while striving for a more cooperative, inclusive, and sustainable global order.

The paper aims to provide a global perspective on U.S. strategic priorities, highlighting how North America fits into the broader geopolitical puzzle. Understanding the rationality behind Trump 47’s policies toward North America is essential to grasp the underlying motivations shaping U.S. actions in the region. By framing these policies within the context of the U.S.’s overarching goals—maintaining global dominance and countering emerging powers like China—this paper seeks to offer actionable insights for policymakers in Mexico and Canada. The objective is to help these nations respond effectively to the challenges posed by Trump 47’s administration, navigating a path that safeguards their interests while adapting to a shifting geopolitical landscape.

The structure of the rest of this paper is as follows: Section 2 introduces classical geopolitical analysis and its relevance today. Section 3 outlines the strategic imperatives driving U.S. policy. Section 4 concludes with recommendations and final remarks.

2. Geopolitics reloaded: The struggle for global dominance

2.1. Geopolitics 101

Geopolitics is the study of how geography shapes power dynamics, international relations, and the strategic priorities of nations. As a discipline, it has been a cornerstone of international relations, offering insights into the interplay between physical geography, economic resources, and political power. At its heart, geopolitics provides a framework to understand the actions of states on the global stage.

From the 19th-century “Great Game” between the British and Russian Empires to Germany’s quest for “Lebensraum” in Eastern Europe during World War II, and the Cold War rivalry between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, geopolitical theories have influenced international strategy and conflict. These frameworks not only explain the distribution of power but also how nations seek to secure and project it over time.

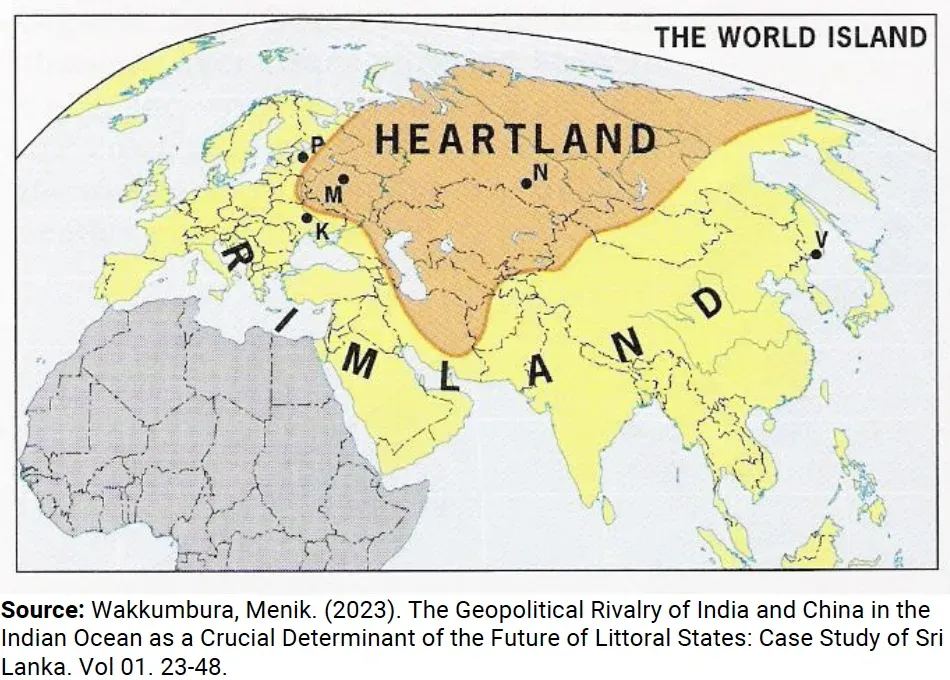

Two foundational theories stand out for their enduring influence: Halford Mackinder’s Heartland Theory and Nicholas Spykman’s Rimland Theory. Writing in the early 20th century, British geographer Halford Mackinder argued that control of Central Asia—the “Heartland”—was the key to dominating Eurasia, a vast landmass stretching from Western Europe to China and encompassing Russia as well as peripheral regions like India, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. According to Mackinder, this region, that today accounts for 60% of the global economy and 70% of the world’s population— represents the gateway to global supremacy.

In contrast, Nicholas Spykman highlighted the strategic importance of maritime power, contending that control of Eurasia’s coastal periphery—the “Rimland,” spanning from the Middle East to South Asia and East Asia—was crucial for achieving global dominance. A Rimland power’s primary objective, he argued, is to prevent any single entity from consolidating in the Heartland and challenging global dominance (Figure 1).

Figure 1 — The Heartland and The Rimland

While Mackinder and Spykman focused primarily on Eurasia, their insights extend to the Western Hemisphere. Mackinder recognized the strategic significance of the U.S., emphasizing the Panama Canal’s role in linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Writing in 1904, he foresaw how this infrastructure would enable the U.S. to mobilize resources across oceans, well before it became a global superpower. Spykman highlighted the U.S.’s unique geographic advantage as a unified continental power with access to both the Atlantic and Pacific. He argued that control over key regions in the Western Hemisphere, such as the Caribbean Basin and the Arctic, would secure the U.S. from external threats and enhance its ability to project power globally, leveraging its maritime capabilities.

Although the tools of influence have evolved, Mackinder and Spykman’s frameworks continue to provide valuable insights into the rise of regional powers, competition for critical resources, global and regional supply chains, and the enduring significance of strategic regions. These theories transcend simplistic economic models by addressing the strategic imperatives that shape policies in a global landscape increasingly defined by competition and declining cooperation.

Spykman’s framework, in particular, profoundly influenced U.S. strategy during the Cold War. As a maritime Rimland power, the U.S. countered Soviet Heartland dominance by fragmenting the Rimland—from the Middle East to East Asia—to prevent the formation of a unified Eurasian coalition capable of challenging America. The enduring relevance of these ideas is evident in the works of Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski, who served as National Security Advisors in the 1970s. Kissinger’s realist diplomacy and Brzezinski’s focus on Eurasian geopolitics both reflect the lasting impact of these theories on U.S. foreign policy. Today, Mackinder and Spykman’s frameworks remain highly relevant as the U.S. faces China as a rising rival and adopts increasingly assertive geopolitical strategies to safeguard its global position.

2.2. The belt, the road, and the navy: Competing visions of global control

The global economic system that emerged after World War II was not a spontaneous cooperative arrangement, but a geopolitical strategy underpinned by the U.S. This system rested on two pillars: the global financial architecture, anchored to the U.S. dollar, and a global logistics network secured by the U.S. Navy’s control of maritime trade routes. These pillars ensured that participation in the global economy hinged on adherence to rules that reinforced by the U.S. During the Cold War, the U.S. faced a competing model in Soviet socialism. However, two pivotal moments—the opening of China in the 1970s and the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s—cemented global free-markets. This ushered in a brief era of triumphalism, epitomized by Francis Fukuyama’s End of History hypothesis, which predicted that free trade would not only foster global prosperity but also drive the spread of liberal democracies.

Yet, beneath its cooperative veneer, the system was profoundly asymmetric. The institutional architecture of the global economy—including the WTO, IMF, World Bank, and BIS—projected the image of multilateral governance, but U.S. financial and maritime dominance gave it unparalleled leverage. These tools allowed the U.S. to marginalize noncompliant nations, cutting them off from financial systems or disrupting physical trade. This credible threat ensured the system’s stability, revealing the so-called cooperative order as a political equilibrium favoring U.S. interests. In recent decades, China’s rise as a political and economic rival has begun to disrupt this equilibrium. By the early 21st century, China had established itself as the world’s second-largest economy, trailing only the U.S. It has since become the leading trading partner for much of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. In defense, China boasts the largest active military force globally, is a nuclear power, and is rapidly modernizing its navy to project power on a global scale. Furthermore, it is striving for leadership in critical emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and green energy (Figure 2).

Figure 2 — US and China Trading Partners

%2016.47.15.png)

Despite China’s departure from its “peaceful rise” doctrine towards a more assertive diplomacy under Xi Jinping, the U.S. continues to wield substantial control over the global economy through its financial and logistical dominance. As of 2024, the U.S. dollar remains the world’s primary reserve currency, accounting for 58% of global reserves, 54% of export invoices, and 88% of foreign exchange transactions. On the logistics front, 80% of global trade moves via ocean routes secured by U.S. naval fleets. Key chokepoints—the Panama Canal, the Suez Canal, and the Strait of Malacca—handle nearly half of global trade and remain under the control of U.S. allies.

Given these advantages, the U.S. should have every incentive to sustain a cooperative global economic system. However, Trump’s approach introduces an inherent tension between the means employed—such as tariffs and economic nationalism—and the longterm

goals of preserving U.S. power. A departure from this framework risks undermining future gains and destabilizing the very system that underpins U.S. power. Yet in recent years, the U.S. has shifted from this equilibrium, engaging in a trade war with China and increasingly leveraging trade policies and tariffs to achieve broader political objectives.

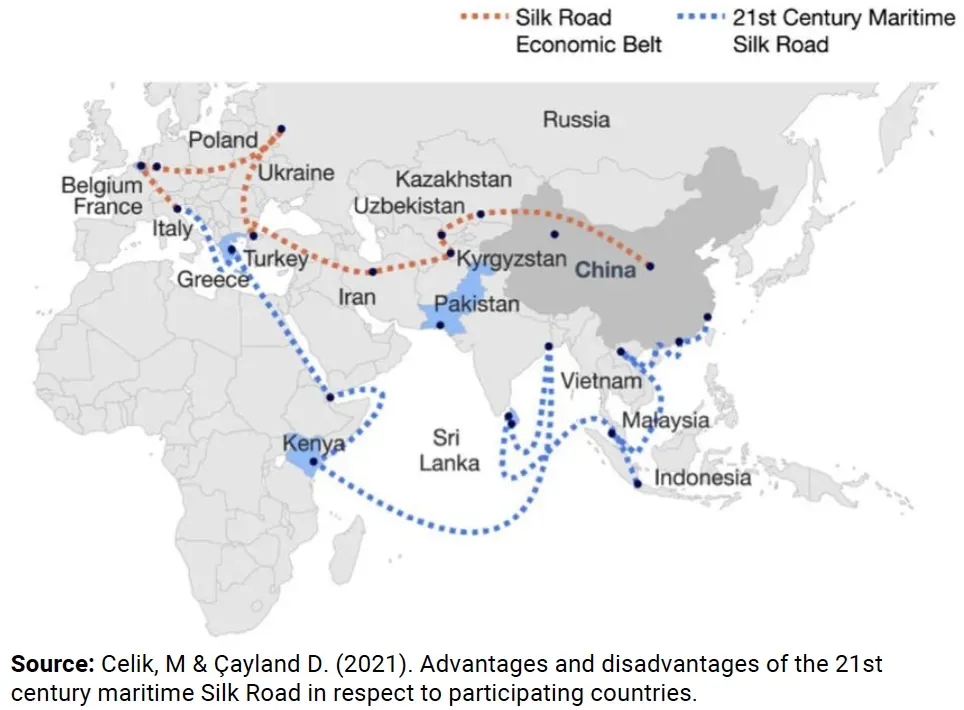

While a comprehensive analysis of the structural factors driving this shift is beyond the scope of this paper, several explanations warrant attention. These include institutional shifts, technological advancements, and the uneven distribution of globalization’s gains, which have exacerbated inequality. However, one often-overlooked explanation lies in geopolitics. China’s economic policies are not solely focused on development; they represent the initial steps of a broader strategy to disengage from a global economy reliant on U.S.-dominated financial and maritime networks. This includes initiatives like the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and efforts to reduce dependence on the U.S. dollar, though achieving a viable substitute remains a significant challenge and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, is a cornerstone of China’s strategy. Initially presented as a plan to develop transportation networks in Central Asia, the BRI now encompasses investments in transport, energy, and digital infrastructure across

more than 150 countries. It aims to link East Asia to Europe via both land and sea, echoing the historic Silk Road trade routes. Beyond economic development, BRI projects also focus on logistics and port infrastructure, particularly along Indo-Pacific Sea routes, creating an alternative to U.S.-controlled maritime trade. Additionally, landbased energy networks could stabilize flows to Europe and East Asia, bypassing conflict-prone chokepoints (Figure 3).

Figure 3 — One Belt One Road

The BRI is far more than an infrastructure project or diplomatic tool. If fully realized, it would create a Central Asian land bridge and a logistics platform capable of supporting Eurasian trade independent of U.S. influence. This network would shift the economic balance of power by enabling Eurasia to operate outside the rules of the post-war U.S.- led global order. Such a transition signals a move toward power-based governance over rules-based systems, fostering accomplishments for some but generating widespread resentment.

China’s BRI exemplifies a modern bid to consolidate Eurasia’s Heartland and periphery into an interconnected system, challenging the maritime dominance central to Spykman’s Rimland framework. In response, the U.S. has adopted a strategy of containment, leveraging its maritime power and alliances to counter China’s initiatives. Partnerships like AUKUS (Australia, United Kingdom, and the U.S.) and the Quad (Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S.), as well as support for Europe against Russia, reflect Rimland-focused actions designed to preserve U.S. geopolitical advantage.

2.3. Fragmenting Eurasia, and securing the Americas: The U.S. geopolitical imperative

The U.S.’ strategic imperatives are shaped by its dual identity as a Rimland power and the dominant force in the Western Hemisphere. This dual role requires the U.S. to balance its global commitments in Eurasia with consolidating its influence across the Americas, ensuring no rival power can challenge its hegemonic position. Through this geopolitical lens, policies that may seem economically irrational often reveal their roots in broader strategic considerations.

As a Rimland power, the U.S.’s primary long-term objective is to prevent any single power from consolidating dominance over the Eurasian landmass—a development that could challenge America. To achieve this, the U.S. has historically pursued strategies that foster a fragmented Eurasia, divided into antagonistic blocs—China, Russia, and Europe—while maintaining a disjointed Rimland periphery. This prevents the logistical and political integration of the continent into a cooperative system that could undermine U.S. influence.

Recent U.S. tactics have centered on measures such as sanctions on Russia and export controls against China. The war in Ukraine, for example, weakens Russia and prevents closer political and economic ties between Europe and Russia. By reinforcing Europe’s dependence on U.S. security, the conflict also impedes the formation of a Europe-Russia bloc that could shift Eurasia’s balance of power. Meanwhile, sanctions aim to degrade Russia’s economy and isolate it diplomatically. However, these actions have brought Russia closer to China, creating a Sino-Russian alignment that combines Russia’s energy resources with China’s manufacturing and technological capabilities.

Yet, the consolidation of this partnership remains uncertain. While Russia has been drawn toward China, the reverse may be less pronounced, as China appears cautious about fully aligning with a partner seen as unpredictable and weakened. Historical tensions also persist, with Russia’s long-standing ambition to lead rather than follow complicating the dynamic. This alignment, while posing a direct challenge to U.S. influence, may also reveal hidden variables or opportunities in the shifting geopolitical landscape.

Confronting both Russia and China simultaneously marks a departure from last century’s strategy when the U.S. strategically played the “China card” against the Soviet Union. The emerging Sino-Russian alignment raises broader risks for anti-American alliances in Asia and Europe. Dual antagonism toward these two powers strains U.S. resources and risks accelerating Eurasian cooperation. Managing alliances has become increasingly challenging: European nations, reliant on Chinese markets, may resist aggressive containment strategies, while East Asian countries hesitate to sever economic ties with China despite U.S. pressure.

Another key shift lies in President Trump’s stated preference to avoid direct U.S. military engagement in Eurasian affairs. This approach emphasizes indirect involvement, leveraging allies to take on more active roles. For instance, European nations could face pressure to counter Russia, while East Asian allies focus on containing China. As President Trump has suggested, this strategy may depend heavily on U.S.’s economic dominance, employing tools such as tariffs and its dominant position in the global financial system to achieve political objectives even if it represents economics losses in the short and medium term.

Technology has emerged as a critical battleground in this rivalry. The U.S. is determined to prevent China from dominating strategic industries such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and electromobility—sectors that are pivotal for both economic power and military superiority. Measures such as export restrictions on advanced chips and reshoring supply chains underscore Washington’s commitment to maintaining technological leadership and limiting Beijing’s ability to leverage these industries for geopolitical gain.

The weaponization of the U.S. financial system highlights the tension inherent in these strategies. Sanctions against Russia risk eroding trust in the global financial architecture anchored to the U.S. dollar. Over time, such measures could spur nations to develop alternative financial systems to reduce their reliance on U.S. influence. The BRICS bloc’s recent proposal to create an alternative currency—despite significant challenges—illustrates this resistance. Paradoxically, these actions may accelerate the formation of the very Eurasian alliances the U.S. seeks to prevent, underscoring the importance of balancing short-term tactics with long-term strategic imperatives.

In the Western Hemisphere, U.S. priorities are aligned with a renewal of Monroe Doctrine. Strategic objectives in North America begin with securing its borders and immediate territory, particularly along the southern border with Mexico. While the border itself poses no direct threat to U.S. global supremacy, it remains a domestic priority critical to political stability. Beyond this, the U.S. seeks to maintain control over strategic chokepoints such as the Caribbean Basin and the Panama Canal, ensuring they remain free from external influence. Emerging areas like the Canadian Arctic, and Greenland where melting ice is opening new maritime routes, are also becoming critical frontiers

for U.S. dominance.

In South America, however, the challenge increasingly centers on China’s expanding footprint, which poses a direct threat to the U.S. A striking example is the Chancay Port in Peru, a Chinese-financed project connecting the Pacific and Atlantic coasts of South America through enhanced logistics networks. While touted as a major economic development, the port has raised alarms in Washington due to its potential dual-use as a Chinese military base. President Trump has already threatened aggressive tariffs on products transiting through Chancay, framing the project as more than an economic venture—it is a geopolitical challenge.

China’s investments in South America extend beyond ports, encompassing mining, energy, and infrastructure. As the primary trading partner for many nations in the region, China is deepening its foothold and shaping South America’s economic and political landscape. In contrast, the U.S. risks marginalization if its strategy remains limited to sanctions and threats. Invoking the Monroe Doctrine alone is unlikely to counter China’s influence in this region; a more nuanced carrot-and-stick approach will be essential.

3. North America: Trump’s fortress or frontline?

3.1. North America’s strategic significance

North America covers more than 16% of the world’s landmass but houses less than 7% of the global population. Despite this, it accounts for over 30% of global GDP, making it an economic powerhouse. The region’s vast resources, industrious population, and advantageous geography underpin U.S. global position. The U.S. shares the continent with Canada and Mexico.

The U.S.-Canada border was last contested in 1812 when Canada was still part of the British Empire. The boundary was formalized in 1846 through the Oregon Treaty, establishing the 49th parallel as the border through the Rockies. Further north, the Arctic is shared by Canada, the U.S. (which purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867), and Greenland, under Danish jurisdiction. The U.S. has maintained a military presence in Greenland since World War II.

To the south, the U.S. shares a border with Mexico, a nation of 128 million people— about one-third of the U.S. population. The border was established in 1848 after the Mexican American War, which resulted in the Mexican Cession, encompassing much of the present-day southwestern U.S. The last military conflict between Mexico and the U.S. occurred in 1914, when U.S. forces occupied Veracruz, but this intervention did not escalate into a full-scale war due to the outbreak of World War I.

Neither Canada nor Mexico poses a direct economic, political, or military threat to the U.S. On the contrary, since the mid-1980s, Mexico has opened its economy and integrated its industrial capacities with the U.S., fostering a robust North American supply chain. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), signed in 1994, served as the institutional backbone for this economic integration. By 2023, Mexico had become the U.S.’s top goods trading partner, with bilateral trade reaching USD 807 billion. Trade with Canada totaled USD 782 billion, while trade with China stood at USD 576 billion. Integrated supply chains drive the economies of the three North American nations, bolstering their global competitiveness. U.S. exports to these partners supported an estimated 1.1 million jobs in 2019.

Despite these benefits, President Trump labeled NAFTA an unfair agreement and initiated its renegotiation. The U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which took effect in 2020, updated NAFTA by including provisions on intellectual property, energy, and small businesses. It also introduced rules on regional content to exclude China from North American value chains and prohibited member nations from entering trade agreements with non-market economies—a clause implicitly targeting China (Figure 4).

%2016.56.57.png)

Following USMCA’s ratification, the U.S. escalated its trade war with China, imposing tariffs on imports. These measures aimed to protect U.S. industries, curb intellectual property theft, and reduce dependency on Chinese imports. However, the broader goal was to contain China’s economic rise. A notable side effect was the strengthening of North American supply chains, with Mexico emerging as the U.S.’s leading trading partner, driven by the nearshoring trend that relocates supply chains from East Asia to North America.

3.2. Borders and beyond: Geopolitical stakes in North America

Under Trump 47, North American economic integration is once again under scrutiny. President Trump has proposed 25% tariffs on Mexico and Canada if they fail to cooperate in securing borders, halting illegal migration, and curbing narcotics trafficking. Such a measure lacks economic rationale, as it would harm all parties, including the U.S. For example, IMF estimates suggest that even temporary tariffs could reduce imports from Canada and Mexico by 5%, with permanent tariffs potentially cutting imports by 20%. These disruptions would weaken the U.S. economy while disproportionately impacting its trade partners.

Nevertheless, the proposal underscores the new administration’s growing willingness to weaponize the economy for non-economic objectives. Securing the U.S.-Mexico border has become a geopolitical priority. Spanning over 3,000 kilometers of rugged desert and mountainous terrain, the border hosts some of the busiest international freight corridors, critical to the U.S.-Mexico economic partnership. Simultaneously, it serves as a major route for the illegal transit of people, drugs, arms, and money.

The ongoing immigration and synthetic drug crises have elevated the southern border to a strategic priority, surpassing purely economic concerns. The lack of effective control at the border highlights a structural vulnerability in the U.S.’s capacity to secure its immediate sphere of influence. Paradoxically, the U.S. has historically placed the burden of border security on Mexico, a dynamic rarely seen elsewhere. This blameshifting illustrates the unique interdependence of the U.S.-Mexico relationship and underscores the need for bilateral collaboration to address shared challenges.

Under Trump 47, pressure on Mexico to control migration flows and fentanyl trafficking will intensify. Failure to address these issues could provoke aggressive actions, starting with economic sanctions. While direct military intervention is improbable, Mexico’s inability to secure the border may lead to unilateral actions and even extraterritorial operations by the U.S.

On the northern border with Canada, strategic objectives are less straightforward but equally tied to geopolitical concerns. Climate change and the potential emergence of ice-free Arctic shipping routes connecting East Asia and Europe are becoming critical considerations. As Canada asserts sovereignty over these routes, significant pressure will mount to exclude China and Russia. Canada’s Arctic ambitions may demand increased defense spending and, in extreme cases, even territorial concessions to the U.S. Recent U.S. declarations of interest in Canada and Greenland illustrate this point.

Containing China remains a key U.S. priority, particularly by preventing its integratio into North American supply chains. Under Trump 45, the U.S. pressured Canada to decouple its economy from China, resulting in a sharp decline in Canadian imports from China since 2023. In contrast, Mexico’s trade with China has steadily increased since 2020—although it is still a fraction of its trade with the United States. As a result, the U.S. is likely to intensify its efforts to pressure Mexico to decouple from China, given China’s growing role as a key trading partner.

The economic dependence of both Mexico and Canada on China suggests that efforts to exclude China from North American supply chains will rely more heavily on coercive measures than the approach required to counter China’s influence in South America, where economic incentives may play a greater role.

3.3. A regional balancing act

The U.S.’s approach to its North American partners reflects a willingness to employ noncompetitive economic strategies to achieve strategic goals. While this approach risks instability within the region, the U.S. is betting on its long-term benefits: securing borders and preventing China from gaining influence in the Western Hemisphere. The assumption that economic interdependence alone will prevent these strategies

from materializing is misguided. U.S. strategic objectives in North America are part of a broader geopolitical effort to forestall the rise of a rival in Eurasia.

However, if Canada and Mexico align with U.S. strategic priorities on defense immigration, and China, the region could move beyond these tensions and refocus on economic goals. A stable, cooperative strategy among the three partners would involve securing North America’s internal and external borders and ensuring that no Eurasian power exerts influence in the region. Such a scenario would unlock the full economic potential of regional integration. North America’s vast resources, youthful population, and unparalleled geography could position it as a haven for investment in an increasingly fragile global environment, consolidating nearshoring and supply chain relocation as enduring trends.

4. From trade wars to power plays: Navigating a divided world

This paper argues that economic analysis alone cannot fully explain the rise of noncooperative economic policies that undermine the global market economy. While globalization offers significant economic benefits, these gains are often insufficient to sustain free markets when strategic goals, such as security and geopolitical dominance, take precedence.

The U.S. has signaled its willingness to accept short-term economic sacrifices to secure long-term strategic advantages and maintain its geopolitical goals. In this context, geopolitics offers a valuable framework for understanding the strategic goals driving these shifts. Economic systems do not operate in isolation but are deeply embedded within political, institutional, and geographic realities. As these underlying structures grow less stable, traditional economic analysis increasingly fails to explain or predict policy behavior.

A critical milestone for North America will be the revision and probably renegotiation of the USMCA in 2026. Considering the hypothesis presented in this paper, this negotiation will go beyond a simple trade dialogue. Instead, it will likely serve as an opportunity for Trump 47 to renegotiate every aspect of the trilateral relationship, aiming to consolidate U.S. dominance in the hemisphere—beginning with its neighbors, clearly. The insights outlined in this paper are essential for policymakers in North America as they prepare for this pivotal process.

4.1. Economic agenda is subordinated to strategic geopolitical objectives under Trump 47

In the current geopolitical landscape, economic benefits are secondary to broader strategic goals, particularly for the U.S. under Trump 47. A lexicographic order of preferences will define interactions, with economic negotiations subordinated to U.S. geopolitical concerns such as border control, immigration, and defense priorities. This approach reflects a carefully curated agenda supported by a “selectorate”—a powerful group of stakeholders with clear objectives backing the administration’s policies.

Policymakers in Canada and Mexico must recognize that U.S. proposals are not erratic but part of a broader strategy to embed structural gains into the emerging global order. Agreements reached under Trump 47 will likely represent strategic wins that future U.S. administrations will defend as pivotal to maintaining its dominance. To engage effectively, North American partners should align economic cooperation with these broader U.S. objectives while advocating for more symmetrical negotiations.

Institutionalizing agreements that balance economic integration with security and immigration imperatives—such as a North American Security and Immigration Agreement—could provide a foundation for long-term cooperation, ensuring alignment between economic and strategic goals. For instance, discussions should not solely focus on Mexico’s responsibilities in curbing drug trafficking but also include U.S. commitments to control arms trafficking and tighten regulations on weapons crossing the border. Such frameworks would foster greater equity in obligations and strengthen regional collaboration.

4.2. Trump will undertake a pragmatic approach

Under Trump 47, U.S. policy will reflect a pragmatic approach that prioritizes his selectorate objectives and respects the hard limits imposed by geopolitical realities. Economic and political constraints will only be relevant as far as they impact these core objectives. However, it is crucial to avoid misinterpretation of this pragmatism. For instance, actions, such as a focus on Arctic security because of climate change impact, should not be construed as signaling a broader commitment to addressing climate change.

This marks a paradigm shift from traditional U.S. policy. Trump 47 will not be engaged in nation-building, spreading democracy, or promoting free-market ideology. Instead, Trump’s pragmatism means negotiating with any actor—regardless of ideological alignment—if it serves U.S. strategic interests. Conversely, ideological closeness does not guarantee preferential treatment. For example, Argentina under Javier Milei, despite ideological similarities with Trump’s administration, should not expect preferential trade agreements if China remains its primary trading partner.

Trump’s involvement in the domestic affairs of allies and adversaries will also lack an ideological basis. For instance, the belief that Trump 47 could act as a counterbalance in Mexico following reforms of judicial and autonomous institutions is misguided. Such involvement will be driven solely by U.S. strategic interests, not a commitment to advancing or preserving democratic norms. Understanding this pragmatism is essential for policymakers to accurately assess U.S. intentions and adapt their strategies to engage effectively with Trump 47’s administration.

4.3. Geography shapes uneven priorities

The U.S. faces distinct geographic realities with its neighbors. Mexico must address challenges such as immigration, drug trafficking, and border security, while Canada’s focus lies on the Arctic frontier, where emerging shipping routes and Chinese ambitions pose significant security risks. These differing priorities make a unified trilateral framework less effective for addressing non-economic issues.

Canada and Mexico should consider flexible bilateral agreements that complement the existing trilateral institutional infrastructure. For Canada, Arctic defense collaboration, including joint efforts to counter Chinese and Russian influence, could bolster its position. For Mexico, an updated framework inspired by the Merida Initiative—adjusted to address current realities—could focus on enhanced cooperation in border security and narcotics control. However, a long-term solution must recognize that both migration and drug trafficking have hemispheric dimensions. Expanding the scope of such a framework to include Central America, as the Merida Initiative once did, could

address the root causes driving these challenges and foster a more integrated regional approach.

4.4. Global priorities drive regional objectives

The U.S. operates under dual imperatives: maintaining global dominance against China and securing its leadership role in the Western Hemisphere. Achieving its goals in North America is more straightforward than its complex objectives in Asia and Europe, where global influence is directly at stake, or even in South America, where China already holds a relevant presence. Moreover, securing the southern border with Mexico presents a more achievable objective compared to addressing emerging Arctic issues with Canada or broader geopolitical goals elsewhere.

If Canada and Mexico align with U.S. priorities on migration, security, and containing China’s influence, the region could achieve greater stability and unlock its economic potential. However, a functional and stable North American alliance will require more carrot and less stick. The U.S.—and Trump 47 in particular—may seek hegemony on the cheap through pressure tactics, but such an approach, risks alienating its neighbors. A geostrategic North American alliance, built on shared benefits and collaborative solutions, could enable the region to consolidate its position as a globally competitive bloc while allowing the U.S. to focus on its broader geopolitical objectives.

4.5. Sustaining U.S. hegemony requires regional cooperation, not just coercion

The U.S. cannot maintain its dominant position indefinitely through threats and indiscriminate weaponization of its economic power against both allies and adversaries. While effective in the short term, such tactics risk backlash over time. To secure its leadership, the U.S. must achieve economic and technological superiority over China, preventing it from emerging as a dominant Eurasian power. An integrated North America is a necessary condition for sustaining U.S. global leadership. Nearshoring presents an opportunity to position North America as a secure and competitive economic bloc in an increasingly volatile world. Achieving this vision will require deeper supply chain integration, infrastructure modernization, and regional innovation. Regional cooperation must prevail to ensure long-term stability and prosperity.

4.6. From Coercion to Collaboration?

To ensure North America’s economic and strategic success, policymakers must adopt a pragmatic approach that aligns economic integration with security objectives. While threats and sanctions may remain part of the U.S. toolkit, fostering regional cooperation will require a balanced strategy that pairs these measures with clear economic incentives. By collaboratively addressing shared challenges and aligning priorities, North America has the potential to solidify its position as a global economic and strategic powerhouse, reinforcing U.S. leadership in an increasingly volatile world.

As North America stands at the crossroads of geopolitics and economic realignment, the choices made in the coming years will define not only the region's future but also its place in an increasingly fractured world. Trump 47’s strategic vision, whether seen as pragmatic or reckless, underscores a stark reality: geopolitics is now the ultimate arbiter of policy. For Canada and Mexico, aligning with U.S. priorities may bring stability but at the cost of sovereignty and flexibility. For the U.S., securing its dominance in North America is a prerequisite for maintaining global hegemony, but this strategy risks alienating allies and sowing long-term instability. The era of globalization as a cooperative ideal is over, replaced by a zero-sum game of power and influence. In this volatile landscape, North America has the potential to emerge as a resilient and unified economic bloc—but only if its leaders navigate the treacherous waters of geopolitics with foresight, pragmatism, and a willingness to adapt to a world defined by both rivalry and interdependence.

The author is professor at the School of Government and Public Transformation, Tecnológico de Monterrey.

Article originally published by the Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.