What is Sustainability and Why is it Important?

Three types of sustainability strategies that companies can implement today

It is difficult these days to pick up a business publication without coming across the term “sustainability,” but the term means different things to different people. Some emphasize its environmental dimension, others its social dimension. Perhaps the best-known definition is the one popularized the by the 1987 Brundtland commission, “meeting the needs of today’s generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs,” but this definition does not provide a guide for action in business terms. In this essay I describe sustainability for business through three different lenses.

Sustainability as a human right in a just society

The 20th century political philosopher, John Rawls argued in A Theory of Justice, that a just society is the one we would design if, blinded by a “veil of ignorance,” we did not know what position we would occupy within that society. We would not know if we would be a well-educated white man, member of an elite in the great commercial centers of Mexico City, Sao Paulo, or Lima, or if we would be a poor, dark skinned, indigenous woman in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, in the Southeast of Mexico, or the Andean range, or a member of a future generation that must live with the consequences of our actions. We must ask ourselves, “are the present-day Latin American societies the ones we would design if we were blinded by Rawls’ ‘veil of ignorance?’”

Rawls’ friend and colleague Amartya Sen added to this definition the concept that justice involves the right of all humans to have the capabilities needed to achieve their life projects. He defined “development as freedom,” freedom to choose a fulfilling life. This implied access to the necessities and capabilities needed for that life—housing, health, education, decent work opportunities, sustainable communities.

Both Rawls’ and Sen’s concepts are embodied in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s). The UN SDGs in were established as responsibilities as national and global goals for 2030. As key members of national and international societies, businesses must recognize their responsibilities to contribute to the SDGs.

We might group the 17 SDGs in five categories of rights applying Rawls’ and Sen’s concepts:

- All human beings have a right to the capabilities needed to determine their own destinies. They have right to health, nutrition, education, and housing in sustainable communities with access to decent employment and social and civic activities,

- All human beings have the right to participate in justly remunerated economic activities. Economic growth should lead to an improvement in workers’ quality of life; work should be dignified, safe and justly compensated; business should deliver goods and services that meet all groups in society’s needs, not just those of its most privileged members.

- Current generations have responsibilities to future generations. Economic growth to meet the needs of current generations cannot come at the expense of the environmental and natural amenities that future generations will require to meet theirs.

- Human beings have a responsibility to non-human inhabitants of the planet and to the ecosystems on which they depend. Non-human species have an economic value to present and future generations and their ethical and moral value is recognized in most philosophical and religious traditions,

- All humans have rights to public and private institutions that are fair, just, strong, and resilient. These institutions must guarantee the equality of rights and opportunities in a sustainable future.

Sustainability as a driver of firm competitiveness

All firms need to make a profit. Firms need to reward their past investors and attract future investors. Their success, be it in traditional markets or in explicitly “social” markets--producing more sustainable forms of transport or microfinance for low-income communities, attracts greater investment to the markets they serve. When these markets are sustainable markets, society benefits from their success as well.

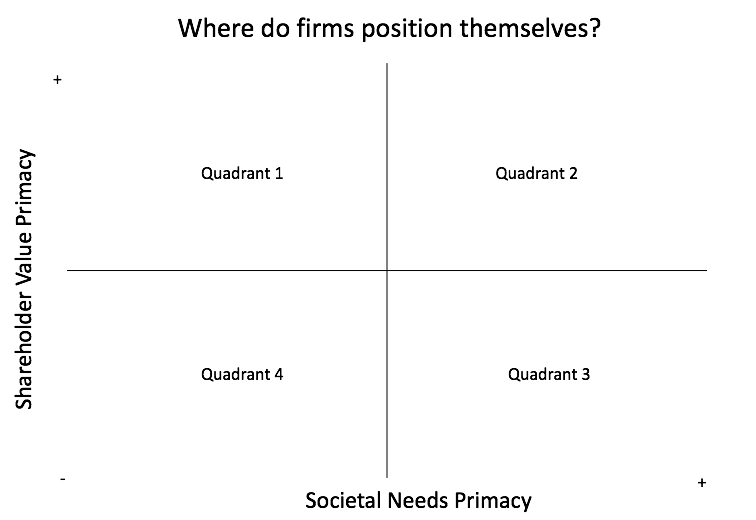

As shown in the figure below how firms assign importance to serving the needs of shareholders or society may differ.

Quadrant 1—some firms such as those associated with the Brazilian investment firm 3G Capital unabashedly put shareholders first. To the extent that they address sustainability, they do so because not to do so would threaten profits. Kraft Heinz Foods, a 3G Capital company suffered a near death experience in 2018 because it failed to innovate to address emerging, healthier eating habits. It is a dangerous oversimplification to say, however, that “ignoring sustainability never pays.” Many firms have found business opportunities to benefit a narrow group of shareholders by ignoring sustainability.

Quadrant 2—firms seek a “shared value” sweet spot where serving shareholders and society intersect. These firms might include Nestle, Unilever, and Ikea whose sustainability purpose is firmly embedded in their operations. As implied above, it is also a dangerous oversimplification to say that “sustainability always pays.” Sustainability programs must be aligned with business objectives.

Quadrant 3--companies explicitly place serving society above serving shareholders. Often these are benefit or B corporations; most such as Patagonia are privately held, others (fewer) such as Danone are publicly held (though Danone’s ouster of its former CEO and board chair under activist investor pressure provides a cautionary tale for B corporations).

Quadrant 4--Lastly, some companies are in quadrant IV where neither society nor shareholders benefit. Sometimes they make “dumb decisions” as when BP repeatedly ignored safety considerations and eventually caused a catastrophic oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Other times, dishonest firm managers place their own parochial interest ahead of those of either society or shareholders (Enron in the early 2000’s).

In general terms, we can think of three types of sustainability strategies businesses might undertake as shown in the figure below:

- Avoid risk: sustainability risks come in many forms—operational, reputational, market. The first, and essential, step is to avoid them. In the early 2000’s despite its efforts to move “beyond petroleum” and mitigate its carbon emissions, BP was repeatedly cited for safety violations. In 2010, a safety “cowboy culture” resulted in the Deepwater Horizon spill that ultimately cost BP over $10 billion (for comparison, about the cost of the James Webb Space Telescope that last week allowed mankind to peer into galaxies that are 13 billion light years away). Fossil fuel companies risk being left with “stranded assets” as at some future point the global economy shifts away from fossil fuels. Tesla, which has done as much as any single other company to contribute to carbon-free mobility, was recently removed from ESG indexes because it is alleged to have mistreated its workforce. Union Carbide went bankrupt because of the Bhopal disaster in India.

- Do things better: Many companies remain in their existing markets and businesses, but they do so more sustainably. Bimbo still makes baked goods, but it does so more sustainably using solar power micro-grids in its California operations. FEMSA and Coca-Cola make soft drinks, but they have goals to reduce their water consumption.

Importantly, many companies today are looking to circular economy initiatives characterized applying “cradle to cradle” thinking under which products and value chains are redesigned to eliminate discarded products as wastes and instead reintegrate them in value chains as raw materials. Addressing the “social” component of their operations, many companies are actively addressing issues of diversity equity and inclusion.

In “doing things better” large firms sometimes create opportunities for firms in their supply chains to provide innovative products and services, to “do better things” (see below). Bimbo and FEMSA may continue to provide bakery products and soft drinks as they have in the past, but they also create opportunities in their supply chains for innovative solar energy suppliers, water conservation companies and advanced recyclers.

- Do better things—the late scholar of innovation Clayton Christensen wrote an important article, in Foreign Affairs toward the end of his life. In it, he and his colleagues argued that business innovation takes three forms: reducing costs by increasing operational efficiency, improving existing products and services to make them more competitive in the market (both of which I characterize above as “doing things better”) and creating new markets, products, and services.

The first two types of innovations are often necessary to remain cost competitive or to protect market share, but they displace existing products (efficiency innovations often reduce employment) and do not contribute to economic growth and employment.

Only innovations that create new markets, products, and services lead to real, sustained economic growth. These innovations focus on previously unaddressed market needs, competing against “non-consumption” in markets where there are no entrenched players. They often become the businesses of the future.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals can serve as a roadmap to the unaddressed needs of the markets of the future. Clinicas del Azucar founded by a graduate of ITESM and MIT provides low cost diabetes treatment, Echale a tu Casa provides low cost housing. The future is in “doing better things” to address using the SDGs as our guide.

Sustainability as a source of institutional legitimacy

In the past half decade populist governments have displaced established governments in the major Latin American economies from Mexico to Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Colombia, Chile and Central America. We can attribute these shifts to idiosyncratic factors—weak institutions and parties, corruption, charismatic populist leaders—or to global trends such as the introduction of social media, but the fact remains: in democracies the people vote, and they are unhappy with the performance of their social and economic institutions.

As Luis Alberto Moreno, former president of the Interamerica Development Bank, points out in “Latin America’s Lost Decades,” Latin America has among the highest levels of inequality in the world in income health and education. It also has very high environmental vulnerability. While as businesspeople we may not agree with the solutions populist leaders propose, we must recognize that their emergence reflect real and deep-set faults in Latin American societies

In an earlier article I argued, agreeing with the authors of the Harvard Business School publication Capitalism at Risk, that unless capitalism addresses sustainability, its survival will be at risk. In Latin America the problem is even more severe; the survival of the basic democratic institutions of society is at risk. Business cannot stand aside.

Points for reflection

- I argue that it is a “dangerous oversimplification” that ignoring sustainability never pays or that “sustainability always pays.”

- Why is this a “dangerous oversimplification?”

- If I am right, what can we do to move sustainability beyond a few very large companies that that are vulnerable to reputation damages if they are unsustainable and a few small social enterprises?

- If we are to meet the UN SDGs by 2030, our efforts to date fall way short of what is needed

- How can we encourage more investment in “doing better things?”

- With whom does business need to partner?

The author is Associate Professor at EGADE Business School and President at The Lexington Group.